Watch podcast episode here.

In this episode we interviewed Professor Nilton Rosário, from the Climate and Air Pollution Laboratory at the Federal University of São Paulo, and Meteorologist Carlos Moniz, from the National Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics (INMG).

Nilton, could you please give a brief presentation of your work at the Climate and Air Pollution Laboratory and tell us about your experience with climate change?

The Laboratory of Climate and Air Pollution (LabCliP) is part of the Department of Environmental Sciences at the Federal University of São Paulo, and is one of the laboratories supporting the Postgraduate Program in Integrated Environmental Analysis (AAI). LabClip’s research is focused on advancing our knowledge of climate processes, in particular those involving the atmosphere and its interaction with continental and oceanic surfaces, and above all understanding the influence that changes introduced by human activities (changes in land cover and use and atmospheric composition) have on the climate.

To be more specific, today we live in spaces (e.g. cities) characterized by climatic conditions that are largely determined by anthropogenic changes. The well-known and harmful heat island effect, common to many cities around the world, is a product of the changes and replacement of natural ground cover by urban structures and materials. In turn, urban spaces, through the emission of gases and particulates, produce an atmospheric composition in their surroundings and beyond that is completely different from that of natural settings. The research I’m involved in seeks to answer questions such as “What is the impact of this combination, changes in the earth’s surface and atmospheric composition, on meteorological and climatic processes? How does it interfere with the interactions between the atmosphere and the surface and what are the implications for temperature, humidity and important processes such as cloud formation and, consequently, rainfall?

We can follow the same reasoning when we think about the large-scale conversion of forest areas, which play a central role in regional and global climate regulation, into large agricultural and livestock areas. In this context, understanding the impacts of the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest is also a central aspect of the research I carry out in collaboration with other colleagues in the lab.

Carlos, can you tell us about the evolution of meteorological variables and the observations of climate change?

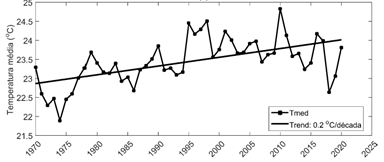

At a global level, one of the main variables where the effect of climate change is evident is temperature, and Cabo Verde is no exception, with a clear tendency for the average local temperature to rise by around 1ºC in recent decades.

But even more interesting than the average temperature is the effect of climate change on the extremes, i.e. minimum and maximum temperatures, where there is a greater tendency for minimum temperatures to rise by around 1.5ºC, a result that points to warmer nights and early mornings.

This is largely because at night, when we no longer have the solar radiation factor, the heat that is emitted by the earth tends to escape through the atmosphere, and this is where greenhouse gases come in, trapping this heat or energy here on Earth, causing local minimum temperatures to rise, even exceeding the increase in the average temperature.

As well as temperature, it is natural to see changes in other variables such as rainfall, where the territorial average has shown downward trends, with recurrent droughts. On the other hand, the number of days with potentially flooding rainfall events (over 20 mm) increased in practically all the stations analyzed.

For other episodes of extreme events such as heat waves and dry haze, the results of the analysis point to a significant upward trend in the number of days associated with these phenomena, directly affecting the lives and daily lives of the local population.

Interannual variation in average, minimum and maximum air temperature, according to data from an INMG reference station.

Nilton, can you tell us the main causes of climate change, including the influence of human activities and natural phenomena?

Natural climate change is part of the history of our planet, which has already undergone drastic natural alterations throughout its evolution. And there are many reasons behind the changes that have taken place in the past. Changes in the configuration of the planet’s orbit and the tilt of its axis in relation to the Sun, changing the amount and distribution of solar energy available to the Earth, are recognized for inducing cyclical changes in the planet’s climate, producing the famous ice ages and interglacials.

Human civilization in general has taken advantage of the relatively stable conditions of the current interglacial period in which we live, with more favorable and stable temperatures that have lasted longer.

Sudden natural climate changes that occurred in the past associated with massive volcanic eruptions can also be cited as examples of natural climate change. It is worth noting that natural climate change and its causes are very well studied and monitored. For example, today there are countless sensors on board satellites that track the energy coming from the sun and reaching our planet.

There are also two important facts to mention in relation to natural climate change: humanity and its social structure as we know it today has not experienced any catastrophic natural climate change. What we do have are cases of important civilizations in the past having collapsed in the face of natural climate fluctuations that destabilized the socio-economic conditions that sustained them, but the planet as a whole has not undergone a process of climate change like the one we are currently experiencing. It is recognized that current climate change has no basis in natural processes.

There are several ways in which we can explain the role of human activities in current global climate change, but we will focus on two aspects that certainly dominate the process: changes in land cover and the basic composition of the atmosphere. The expansion of urban-industrial areas and areas devoted to agricultural activities has produced changes in the earth’s surface on a scale never seen in human history, with the removal of large areas of natural vegetation cover. This has radically changed the exchange of energy between the surface and the atmosphere, consequently producing significant changes in climatic conditions around the world. Alongside the expansion of urbanization and agricultural areas, the industrial revolution introduced the large-scale burning of fossil fuels as the main source of energy to meet society’s needs. As a result, a gradual process of greenhouse gas (GHG) accumulation began, especially CO2, a by-product of burning fossil fuels.

Between 1850 and 2020, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere increased from 280 parts per million (ppm) to over 420 ppm in less than 200 years. Meanwhile, the average global temperature increased by more than 1 degree Celsius. Changes of this magnitude, in such a short time, are not observed in records relating to natural climate change. It was only a matter of time before the implications of the accumulation of CO2 and other GHGs emitted by our activities came to light, as the basic science explaining their climatic effects, such as planetary warming, had long been established. The GHGs present in the atmosphere are efficient at absorbing the radiative energy emitted by the surface of our planet, which is why they are called greenhouse gases, the obvious result of which is the warming of the planet. Therefore, the ongoing global climate change, the main feature of which is global warming, has its origins directly linked to human activities, especially CO2 emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and large-scale biomass burning.

Nilton, what are the immediate and long-term impacts of climate change globally and in Cabo Verde?

In global terms, the primary impact is an increase in the temperature of the atmosphere and oceans. This already implies a destabilization of the climate system, since a new temperature configuration will require the planet to seek a new equilibrium condition. Naturally, in this process, the climate system will produce extreme responses such as more intense heat waves, more severe storms, extreme droughts, among other possible extremes since there is an excess of energy accumulated on the planet. The impacts of these extremes are immediate, and indeed around the world there has been an increase in extreme weather and climate events.

The rapid increase in global temperature, associated with these extremes, has put enormous pressure on terrestrial and marine ecosystems, making it difficult for them to gradually adapt to the new climate regime. We know that, despite technological advances, society is still extremely dependent on ecosystem services. However, it’s not just natural systems that are in danger; our food production and water security structures also face the challenge of adapting to climate change. The difficulties have already been seen with an increase of just over 1 degree Celsius, which makes it clear that scenarios of an increase of more than 2 degrees have everything to be catastrophic, hence the need to classify the context as a climate emergency.

Cabo Verde is subject to all these aspects of environmental degradation mentioned above, and our reality already shows a transition to a warmer climate regime (temperatures have risen by more than 1 degree in the last five decades in Cabo Verde) with a significant increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme events, as already identified in the country’s climatological records, both in relation to heat waves and extremes of rainfall. These environmental stressors certainly have an impact on the country’s socio-economic fabric. Both fishing and agriculture depend heavily on climatic conditions and the unpredictability generated by a new climate regime, marked by extremes, increases the vulnerability of the communities that depend on these activities and Cabo Verdean society in general. The threats to the physical integrity of communities, especially the most vulnerable, have certainly increased, and could worsen, in the face of scenarios such as excessive heat and torrential rains of greater intensity.

Even the tourism sector, which benefits in some way from the heat, is at serious risk given the potential for disruption produced by more intense tropical storms, and the challenge we have nationally in terms of water and energy security. Mass tourism in a warmer environment demands a lot of water, energy and strong food logistics, aspects that are in the crosshairs of the effects of climate change. In addition, investment in tourism in Cabo Verde is concentrated in coastal regions, which represent a serious risk in the face of rising sea levels, and we have already had examples of tidal surges associated with tropical storms causing significant damage. Our status as an island country that is still developing puts us in an even more vulnerable situation, which extends to our unique biodiversity.

Carlos: What is INMG’s role in monitoring these impacts?

The Institute plays a fundamental role in monitoring the impacts of climate change, especially the consequences that have already been observed in terms of extreme events, such as episodes of heat waves, dry haze and tropical depressions that bring torrential rains, floods, strong winds and sea turbulence. The Institute has a duty to monitor and draw up forecasts when we have situations of extreme events and to transmit the information in a clear, timely manner to the population and the media, so that we can mitigate the loss of material damage and so that there is no loss of human life.

More than that, the Institute is currently Cabo Verde’s Focal Point for Climate Change at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), bridging the gap between that organization and the country on the entire negotiation process and the decisions adopted. The INMG is also the Focal Point of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a technical scientific body of the Convention whose main objective is to synthesize and disseminate the most advanced knowledge on climate change affecting the world today, specifically global warming, pointing out its causes, effects and risks for humanity and the environment, and suggesting ways to combat the problems.

As Focal Point of the Adaptation Fund, the INMG monitors the entire process of financing international funds for adaptation to climate change and its implementation in the country. In addition to the competencies mentioned above, the National Institute of Meteorology participates in the drafting of various strategic documents for the country on climate change and environmental sustainability, such as the NPA (National Adaptation Plan, vision 2026), NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris Agreement, vision 2030), Roadmap for the implementation of the Paris Agreement in Cabo Verde.

Nilton, looking to the future, what scenarios do we have and what are the projections for the main climate variables such as air and sea temperature and precipitation and the average sea level?

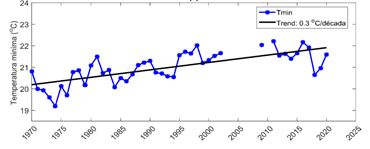

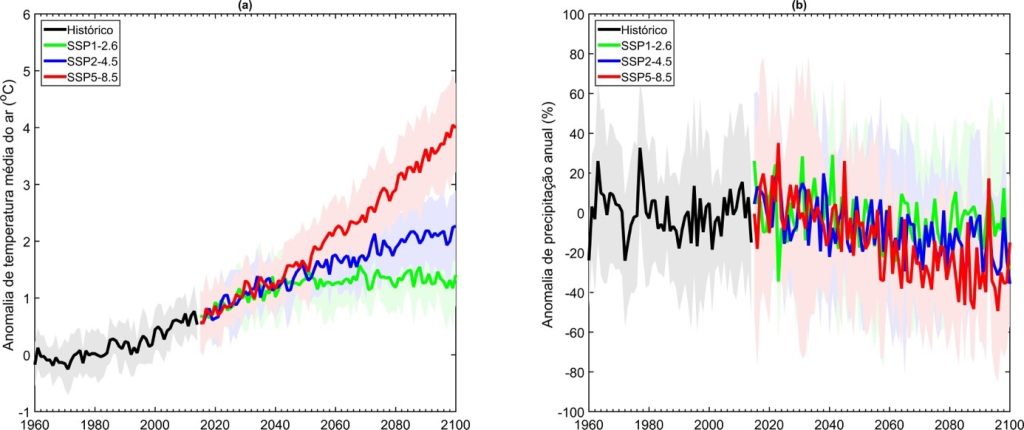

Future climate projections are generally articulated on the basis of three main economic development scenarios: the ideal one, based on drastic reductions in GHG emissions and ambitious sustainable development practices and energy transition to cleaner matrices, which would lead us to keep the global temperature increase below 2.0 degrees Celsius by 2100, another intermediate scenario characterized by the use of a series of technologies and strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in which the increase would be between 2.0 and 3.7 degrees Celsius and, finally, the most critical, in which things remain as they have been in the past, i.e. development based on unrestricted consumption of fossil fuels with no ambitions in terms of sustainable practices, which would lead to an increase in the average global temperature of over 5.0 degrees Celsius.

As is the case in other parts of the world, the air temperature in Cabo Verde, both the average and the extremes (maximum and minimum), is showing a significant upward trend and is consistent with the most critical scenario, an increase of over 1 degree in a few decades. Therefore, even if extremely restrictive measures are adopted in relation to emissions, through development aligned with good practices such as the energy and sustainable transition, it will be difficult for the planet to keep warming below 2.0 degrees Celsius by 2100. On the other hand, if humanity insists on its dependence on burning fossil fuels, without any sustainable ambition and with aggressive development practices, temperatures in Cabo Verde, being conservative here, could reach an increase of up to 5.0 degrees Celsius by 2100.

The temperature of the ocean around us will certainly be more than enough to fuel severe tropical storms and certainly hurricanes. In addition, the ocean stratification resulting from the strong warming will pose major challenges for the vertical circulation of marine nutrients, which will impact marine biodiversity itself, an important source of resources for our reality. Whatever the scenario, rainfall in Cabo Verde is projected to decrease. Obviously, in the most critical scenario, these trends are reinforced, when annual rainfall is projected to fall by around 30%. Rainfall, which is already irregular, tends to become more irregular and droughts more prolonged, according to climate model projections. Precipitation is one of the most challenging variables in climate projections, but the models consistently indicate persistent drought scenarios.

The thermal expansion of the oceans will lead to rising sea levels with catastrophic implications for the coastal regions of several countries. In Cabo Verde, projections point to an increase in the average sea level of between 40 and 100 cm by 2100, which puts several of the country’s coastal regions at risk. Numerous biological processes, both marine and terrestrial, are regulated by temperature. In Cabo Verde we have the classic example of sea turtle reproduction. With warming, these processes could be severely affected, triggering environmental imbalances in various ecological niches, which will certainly affect the environmental services on which we depend. The accelerated transition in climate patterns will pose difficulties for the adaptation of various living species. A warmer planet means excess energy accumulated in the physical environment, which creates conditions conducive to climatic extremes, more severe storms, more intense droughts and more. These results have already been observed, and as the planet continues to warm, the more intense and frequent the extremes will become. In Cabo Verde, we expect to see trends similar to those observed on a global scale. However, once again, our status as a developing island state, with serious adaptation challenges, places us in a condition of high climate vulnerability, which will be extremely aggravated if humanity persists on the path of the most critical socio-economic development scenario, i.e. the one that puts us on course for an increase of more than 5.0 degrees Celsius in relation to the planet’s average temperature.

Carlos, what paths can we take to cope with these impacts and adapt to the changes?

As a Sahelian country and a small island state, Cabo Verde is extremely vulnerable to climate change, and has long dealt with the unpredictability of its hostile climate, but it has stood out for its good governance, level of development and broad integration of equality issues into its policies and practices, despite the erosion that the harsh climate causes to its environment, society and economy. The scarcity and irregularity of rainfall causes cyclical droughts, the permanent water deficit and marked desertification, limited access to water and the geomorphology of many of the inhabited islands, pose significant risks to the agricultural sector and food security, causing devastating effects on the country’s fragile ecosystems.

Mitigation and adaptation have been two key concepts when it comes to finding solutions to climate change, where mitigation is seeking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from activities and looking for sustainable solutions, and Cabo Verde is a country that emits little greenhouse gases and has a low contribution of around 0.002%, but it is still important for Cabo Verde to invest in the energy transition and clean, green energy so that we are no longer dependent on oil derivatives, which would also have an effect on the local economy.

But really for Cabo Verde, an island country, the issue of adaptation in terms of climate resilience is the fundamental concept to be implemented, in terms of leaving behind practices that are no longer sustainable and seeking to adapt so that the consequences of the effects of climate change are minimized. At a local level, politicians, institutions and other entities must try to respond to these problems, such as urban restructuring to combat floods and heat waves, seeking agricultural solutions such as desalinization of seawater, and raising awareness and literacy about this global phenomenon of climate change. At a global level, Cabo Verde has already taken significant steps in this direction, integrating the issue of climate resilience into its 2020-2030 Ambition, ratifying the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, submitting three National Communications and their respective Greenhouse Gas Inventories, two Nationally Determined Contributions, With very ambitious plans for mitigating and reducing GHG emissions, in 2021 it submitted the first National Adaptation Plan (NAP), in an effort to promote transformative change in the entire planning and budgeting process and also in current environmental, social and economic practices, and to increase its capacity to absorb climate shocks, which are expected to become even more intense and frequent.

Nilton, what advice would you give our listeners to adapt to the impact of climate change on their daily lives?

First, try to be well-informed about climate change, its causes and consequences. Look for official and reliable sources of information, avoid spreading Fake News: the climate emergency is a reality and many lives depend on being able to cope with it. The more we know about it, the more empowered our communities will be.

Help those most in need, especially in extreme weather and climate scenarios, as we are already experiencing the consequences of global warming. Adopt sustainable practices, for example, avoid using vehicles based on fossil fuels when there is a more sustainable alternative, don’t waste water and food. The production of water and the logistics involved in the production and transportation of food also contribute to GHG emissions and therefore to the worsening of global warming. Get involved with your communities in identifying local and natural solutions to the challenges posed by climate change, preserve green areas, contribute to their expansion as they play a fundamental role in mitigating the effects of heat waves and landslides during extreme rainfall events and in preserving our biodiversity. As Mahatma Gandhi would say, be the change you want to see in the world. We only have this planet, it offers everything we need, let’s make sure it stays that way, generous also to future generations.

Author

Niton do Rosário,

LabCliP

Carlos Moniz,

INMG